A Glimpse of the Boat that Gave Ernest Hemingway a Lifetime of Stories, Studies, Adventures and Fishing

The identity of a boat mirrors its owner. It’s a matter of time and interest, shaped further by needs and desires, which can define the vessel as one dedicated type, or show how “she” takes on multiple roles over a lifetime on the waves. Or both can be true. This was the case for Pilar – the boat once owned by Ernest Hemingway, which operated in the waters off Key West, Bimini, and Cuba, for 27 years.

"It is a truism that boats take quite a bit from their owners. They can also give back over a lifetime of use, in a hundred different ways, but in Hemingway’s case, these can be narrowed down to four: Fishing, Adventure, Stories, and Studies."

It is a truism that boats take quite a bit from their owners. They can also give back over a lifetime of use, in a hundred different ways, but in Hemingway’s case, these can be narrowed down to four: Fishing, Adventure, Stories, and Studies.

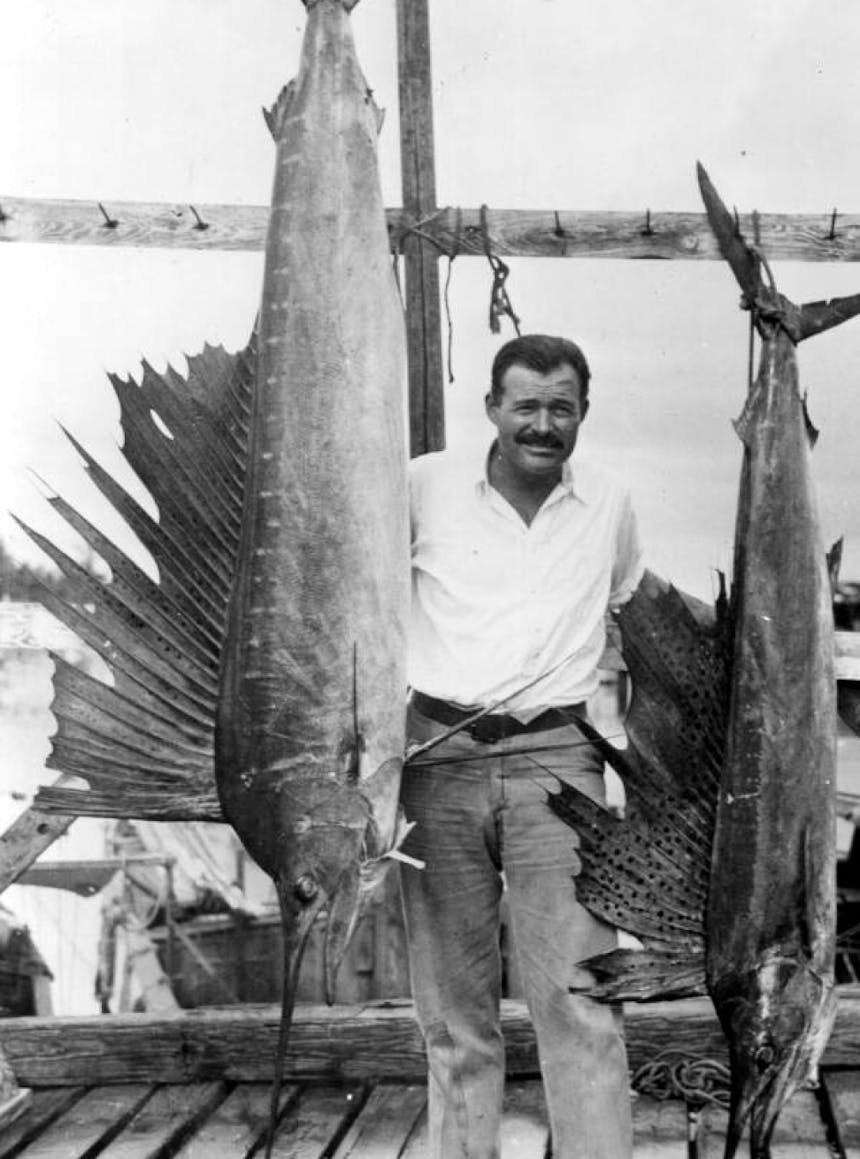

The first was born out of a passion for big-game fishing – marlin, tuna, sailfish – that began with an introduction to saltwater fishing life in Key West during a visit in 1928. Hemingway moved there with Pauline Pfeiffer (his second wife) in 1931. Three years later, Hemingway purchased a new boat: a customized “Wheeler Playmate” motor yacht built at the Wheeler Shipbuilding yard at Coney Island. She was christened Pilar – after Pauline, and as it also happens, a female partisan leader character of the same name from his novel For Whom the Bell Tolls.

touting a Thompson submachine gun and a case of grenades, as he patrolled the waters of the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico in search of German U-boats on the prowl... but for years afterward, the Thompson remained on board as a tool employed by Hemingway against sharks seeking his trophy marlins and tuna.

The fishing that followed was interrupted only by World War II, which marked a time of Adventure when Pilar underwent a transformation to a sub-hunter/chaser with Hemingway at the helm, touting a Thompson submachine gun and a case of grenades, as he patrolled the waters of the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico in search of German U-boats on the prowl. Both 1942 and 1943 passed without incident, but for years afterward, the Thompson remained on board as a tool employed by Hemingway against sharks seeking his trophy marlins and tuna. Later, Adventures of another sort followed the wake of the boat, as Hemingway brought aboard Hollywood movie stars, artists, fellow authors, and celebrities to ply the warm waters off Havana, Key West, and Bimini.

Hemingway sought to learn about his quarry, bringing this knowledge to the benefit of ocean researchers like Charles M.B. Cadwalader, and Henry Fowler, both from the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. It was through these efforts that the different species of marlin were identified. Journals meticulously kept by Hemingway provided more insights into sharks, especially those found in Cuban waters.

But the Fishing remained front and center, for Pilar and her master. Hemingway gained a worldwide reputation as a top salt water fisherman. He captured a world record for seven marlin caught in a single day. And he is credited with developing a technique to quickly land fish, such as prized tuna, to prevent sharks from ruining them during the catch. Another technique not so easily embraced by others, was his use of the Thompson to eradicate such sharks: this had mixed results, as the painter and fellow fisherman Mike Strater could attest to when his 1,000-pound marlin was chewed up during a Pilar trip in 1935. At underscored Hemingway’s lifelong attitude about what it took to be a success, whether this was a struggle with the real natural world, or a reflection of his views of the world as seen through the eyes of the characters of his written works.

Tales of fishing abound in Hemingway’s written work, with The Old Man and the Sea (1953) considered a pinnacle of such efforts. As he told Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, he regarded the sport of fishing for those times “in between” his writing, “when you can’t do it.”

The Pilar was given to his longtime fishing companion and captain, Carlos Gutierrez, after Hemingway decided to leave Cuba for good with his fourth wife, Mary Welsh Hemingway, on July 25, 1960. The boat’s lifetime of service on the water was soon at an end. Since that time, the vessel has been part of a public display in Havana, Cuba, at the “Hemingway Museum.” An ignoble end for the vessel, followed by the passing of her longtime master just a year later.

[Suggested reading: Hemingway on Fishing by Ernest Hemingway, edited and with an introduction by Nick Lyons (2000)]