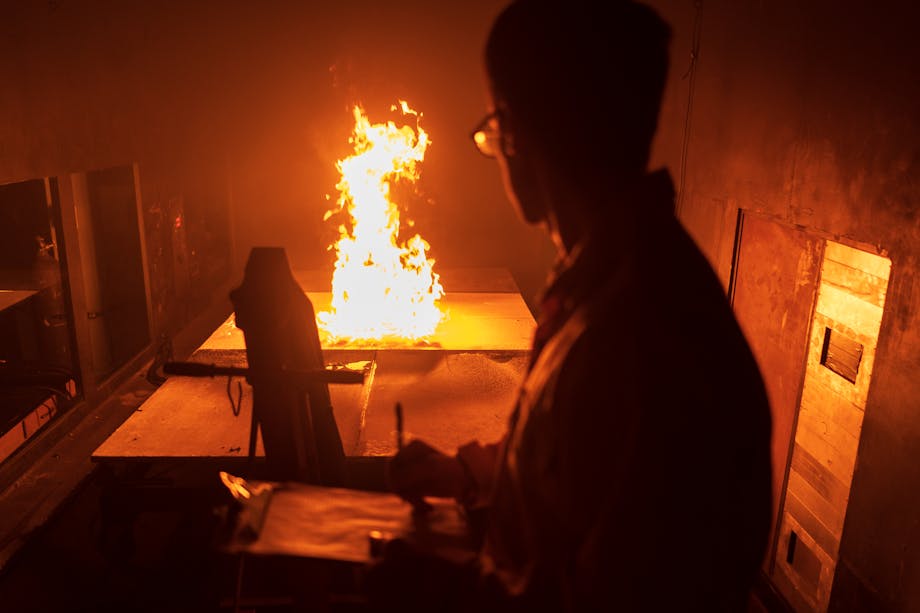

There’s a wall of fire 12 feet away. Ponderosa pines burn to a roar. Like a jet engine ramping up for takeoff. Flames ignite branches and tufts of green needles on their way up the trunks.

Hotshots, smokejumpers and other Forest Service employees stand nearby. They’re not here to put the fire out. They started the fire. With torches. They’re here to make sure it burns.

“This is a forest forest,” says Dan Hoswald, the USFS burn boss guiding the team. “Putting fire back into the ecosystem is huge.”

A critical role in USFS’s stewardship of our national forests is fire management. During the summer fire season, 10,000 wildland firefighters are employed to fight fires – 98 percent of which are contained soon after detection. Others are remembered for generations. In many cases, some of that success in keeping wildfires from causing unwanted damage is due to the proactive use of prescribed fire.

"From a distance it can look like another wildfire, which we’ve come to view as a disaster, chaos. But it’s not chaos. It’s management. And it’s essential."

“There’s an over-abundance of trees,” Hoswald says. “That’s where our problem lies – not letting fire take its course, and putting out fires for 60, 70, 80 years. That’s why we have these catastrophic events, and everybody’s upset. The real deal is that this needs to happen.”

For thousands of years, forests evolved with the help of fires. Fire is essential to forests like the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest. It releases nutrients into the soil and improves the habitat of plants and animals. It also clears out excess brush, limbs, dead trees and other fire fuel on the ground.

But an era of intense fire suppression has left many of America’s forests swinging out of equilibrium, resulting in forests with far too much fuel and a propensity to burn in catastrophic and destructive events. That’s why in the offseason, the USFS lights prescribed burns intentionally. It’s a tool in its arsenal to help keep the unplanned fires more manageable and less dsstructive.

When we look at a forest after a fire, we see burned trees. The truth is far more complicated. Healthy forests with a natural fire regime can be reinvigorated with low-intensity fires that return every few years, shaping a community of plants and animals that evolved with fire just as the Arctic evolved with snow and ice or the rainforest with rain.

“Fire is like whiskey,” says Ali Dean, a member of Central Oregon’s Fire Management Service. “You don’t judge it as soon as it comes out of the still. You got to put it in the cask and let it do all of those magical interactions with the charred wood. The fire is just the catalyst for that, but it’s all these interactions that happen later on that produce what you want.”

Today’s burn will cover 100 acres. Teams of wildland firefighters line the fire boundary to make sure flames don’t jump over its edges. Other teams ignite the fire with special attention to the timing and placement of their ignition patterns to burn the material they want while keeping the fire controllable.

As the fire grows, it spreads in a patchy way. That’s good.

The key to a good fire is to affect the landscape in a diverse way. It creates a forest that’s dynamic, with some spots ripe for new growth and others that hold a bit more brush and a thicker understory.

From a distance it can look like another wildfire, which we’ve come to view as a disaster, chaos. But it’s not chaos. It’s management. And it’s essential.

“We’re restoring a natural process and trying to help the forest get healthy again,” says Dean. “It really feels like we’re part of something that is natural and beautiful and has been unfortunately suppressed for far too long.”