The 210th Air Rescue Squadron, nicknamed “The Second 10th,” is an elite peacetime and combat search and rescue (CSAR) unit based in Alaska that’s on call for its citizens 24/7/365. Regarded as “the Guardians of the North,” the unit has saved thousands of natives stranded in remote terrain, brutal snowstorms, and icy waters along the coast. Like most highly respected and capable units, their lessons and formation emerged mostly out of necessity but sometimes on a whim. This historic unit began with the now-disbanded World War II unit called the 10th AAF Emergency Rescue Boat Squadron (10th ERBS). In its infancy, it underwent several name changes, known at different times as the Air Corps Marine Rescue Service and the 924th Quartermaster Boat Squadron [Aviation].

The unit operated essentially armed rescue boats, responsible for going into very chaotic environments and picking up downed allied pilots in Alaska, along the Aleutian Chain, and on the Kuril Islands. Although they were limited to this Area of Operations (AO), their sister “Crash Boat” units deployed to the Pacific and launched other combat missions, including the infiltration of spies and saboteurs into China and extracting known United Nations personnel. After the war, the unit disbanded and was transformed into the 10th Air Rescue Squadron (ARS) in 1946 at Elmendorf Field.

Shortly after the squadron was formed, Joe Redington Sr., an enlisted Airborne instructor, WWII veteran, and later the “Father of the Iditarod,” secured a government contract in 1949. The US Air Force recognized that jump-qualified dogs and sled mushers could provide a capability in search and rescue, as well as perhaps other commando or intelligence capacities, as evidenced by the long and revered history of the use of Alaskan sled dogs in France during WWI, where their role was so critical that three dogs were awarded France’s highest honor: the Croix de Guerre (equivalent to the Medal of Honor).

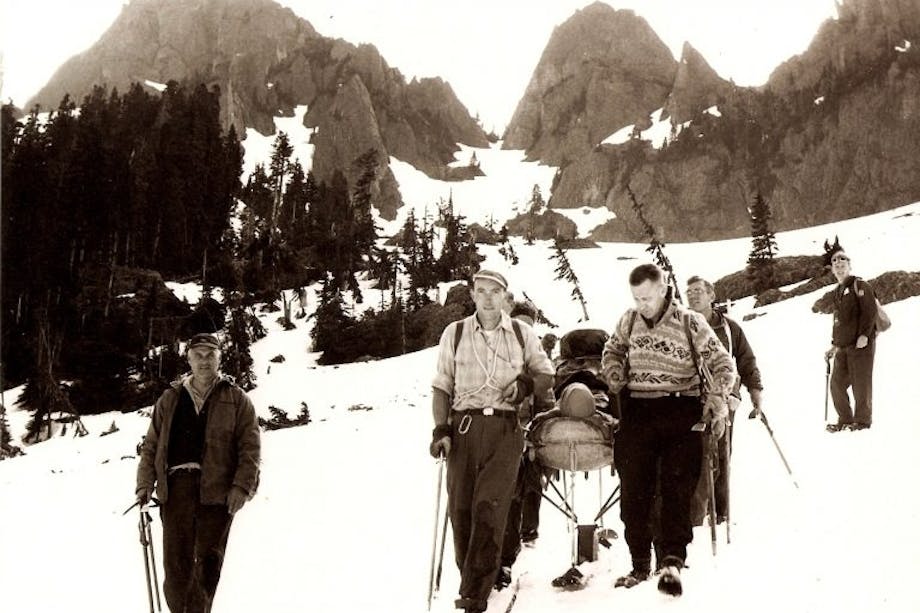

During the Second World War, Major Marvin “Muktuk” Marston of the Alaskan Territorial Guard scouted Japanese mobilizations and helped transport firearms, supplies, munitions, and information to remote areas that only dog teams could access. They were certainly valued because there is no price tag on primal instincts like the nose of a husky or malamute. Before the dogs could participate, they had to successfully complete five jumps to receive their jump wings, just like their human counterparts. Master Sergeant Walter Millard completed over 250 jumps, many with dogs that would then clip into sleds once on the ground.

The ARS in the ‘40s and ‘50s was still primitive, but a paradigm shift in technology improved their response times. Charles Weir was among the first helicopter pilots in the country, and he tested the unit’s mettle daily. At first, helicopters were never intended to fly at night in complete darkness or in frigid temperatures that froze the instruments. “Once I had to spend the night at a rescue site,” Weir told Airman Magazine. “There was no self-support gear then, and I knew the engine wouldn’t start in the morning if the battery was too cold. So, I improvised. To keep the battery warm, I took it out of the chopper and put it in the sleeping bag with me. Every few hours, I went out to the chopper, plugged in the battery and ran the engine for a few minutes before taking it back to the sleeping bag with me. That’s the only way I got out of there in the morning.”

The crash of a TB-29 Superfortress on November 15, 1957 proved why helicopters are critical in aiding victims stranded in isolated terrain. Today, the wreckage site can be found while traveling on foot, which takes on average six to eight hours for an experienced hiker. The weather can be unpredictable, just like the crew experienced on that fateful day.

While on a routine mission calibrating radar, bad weather and confusion caused the bomber to stray off course and crash onto a glacier near the Talkeetna Mountains. Six of the ten crew members were killed on impact, and the survivors braved harsh winds for two days while they waited for rescue, wrapped in sleeping bags and parachutes. A Piasecki SH-21 Workhorse, a SAR helicopter of the 10th ARG, responded and rescued the survivors from certain death.

The 10th ARS merged into the 10th Air Rescue Group (ARG) in 1952 and later became the 71st Air Rescue Squadron, where modern-day rescue tactics, techniques, and procedures in the arctic were pioneered. On October 4, 1980, a 427-foot Dutch cruise liner called the Prinsendam caught fire in the engine room at midnight 120 miles south of Yakutat, Alaska.

An urgent distress call raised the alarm, and the 71st ARS led a coordinated rescue effort along with the US Coast Guard and Canadian forces. “The training and expertise of the Air Force pararescue men [PJs] were responsible for the survival of passengers,” commented Rear Admiral Richard Knapp. “It is notable that we were forced to rely on another agency to provide these personnel.” This event showed the need for the Coast Guard to develop a rescue swimmer program, proving that the Air Force was highly effective in its expertise.

Today the 210th Air Rescue Squadron of the Alaska Air National Guard is one of the busiest search-and-rescue units in the world. Alongside 211th ARS and 212th ARS, as a part of the network of the 11th Air Force; Special Mission Aviators, PJs, and Combat Rescue Officers act as guardian angels for those in need. They employ every asset in their arsenal from lessons learned from their famed past to technological ingenuity that helps them successfully rescue thousands of people each year. For those who become trapped in glacier crevasses, are caught in snow-storms during the Yukon Quest, or need a lifeline, the ARS are on call, waiting to respond.